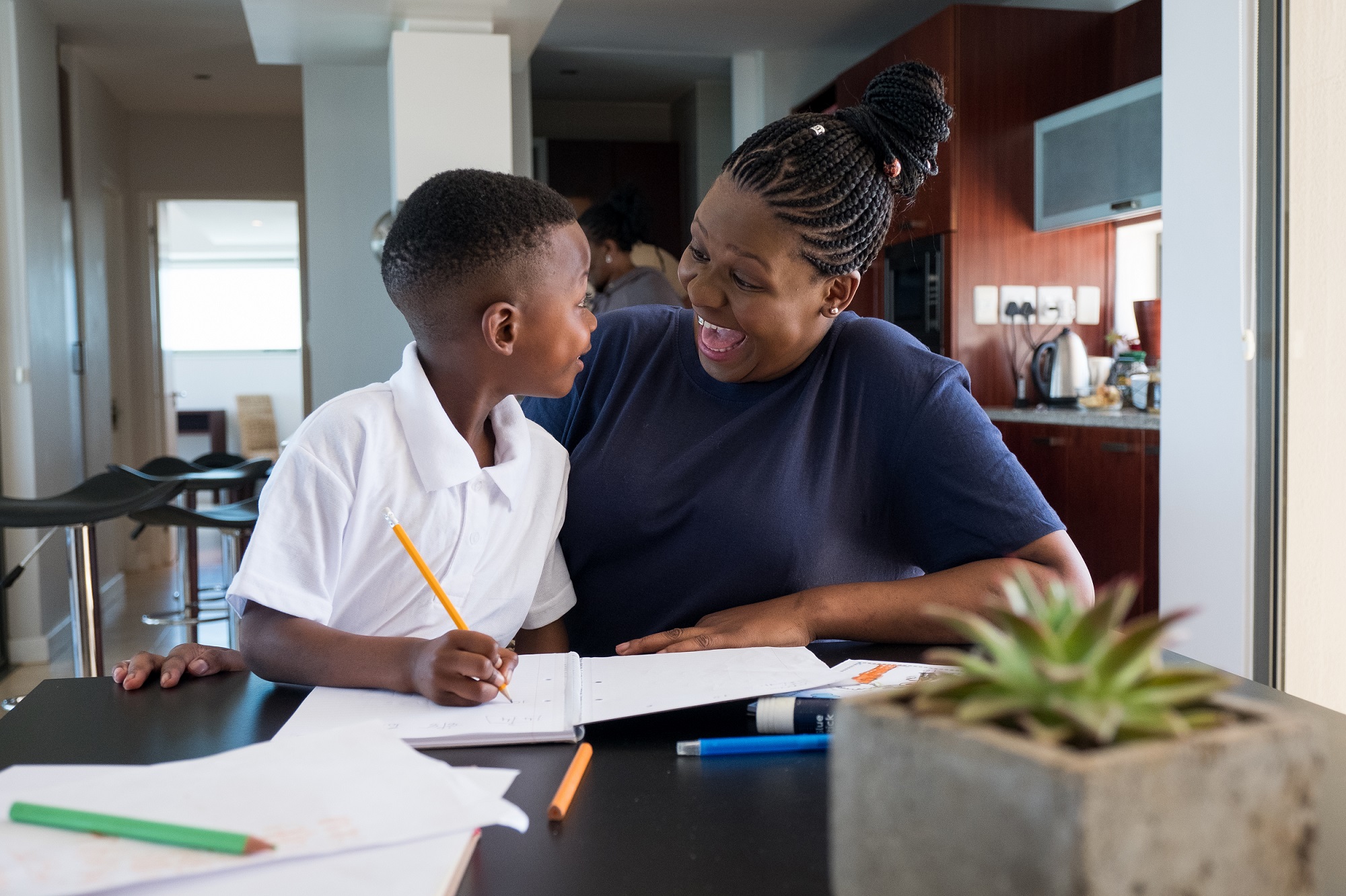

Giving your children the education they need to build a successful future is something most parents strive for. Samke Mhlongo shares the various options available for planning for your child’s education, and how they work.

“At least you don’t have to pay school fees, mngani!” That is what my childhood friend says whenever I complain about how tough life is. And, she’s right! With Old Mutual estimating that by 2025, the average cost of one year of education at a public primary school will be R63 300, R154 900 at a private primary and R258 700 at a private high school, I sure am glad that my divorce settlement absolved me of all education-related costs. But, what happens should my ex-husband no longer be in a position to pay for them? What happens should I find myself in a position where my kids look to me as the sole provider of their education costs? Well, the thought alone has raised the impetus with which I need to search for a second husband. But, in the meantime, I turned to the experts and my social media community for some insights.

Is an education policy still the way to go?

In my parents’ day, education policies were the buzzword when it came to financing education costs. I was surprised to learn that they still exist. Gavin Lewin, independent certified financial planner at Premise Consulting, explains that they have never been anything more than endowment policies with the name “education” attached to them. “Education policies are basically unit trusts funds with a specific investment term, marketed as savings tools for education purposes. However, you can use the proceeds of these policies for other purposes such as a house deposit or towards buying a small car. There is no specific quality unique to them,” he says. Investment management firm Allan Gray’s website provides another distinction between education policies and unit trusts. It notes that education policies have set premiums and penalties for making changes to them, stopping contributions and/or making early withdrawals. The inflexibility that comes with education policies, and the additional costs for built-in features such as life insurance and minimum guaranteed returns, may be the reason this investment product isn’t as popular with our generation as it was with our parents. Our generation has more options and access to information. To test this theory, I turned to my social media community to find out if education policies were still a “thing” or if other means to fund education were being used. The responses ranged from those that were predictable to sophisticated and downright hilarious ones! Don Dlamini, for instance, is a brave man who has opted to home-school his children. On the other hand, banking professional Dudu Nhlabathi-Madonsela has taken out share options for her son. Thabiso Shai shared on Twitter that he pays his children’s daycare and primary education from his salary, and will use the proceeds from their education policy to fund their high school and tertiary fees. But, what happens should you no longer be in a position to make monthly contributions towards an investment, whether due to illness or death? It’s quite prudent to consider the following options to safeguard your children form the harsh negative effects of these eventualities.

SEE ALSO: Planning for a baby

Education insurance vs trusts

“Education Insurance is a type of insurance that pays for a child’s education in the event of the parent’s death, disability or severe illness”, Gavin explains. Another way to fund the cost of education after the passing of a parent is through a trust. Trust specialist and director of Kgolema Financial Consultants, Kgomotso Masongoa, says there are two types of trusts. These are inter vivos where the founder establishes while alive, and testamentary trusts that come into existence upon the death of the founder, say via a will. Although they can both be used to provide for a child’s education after the parent’s death, the proceeds from education insurance can only be used for educational purposes. On the other hand, the assets in a trust are disbursed per the stipulations of a will. Another difference is that education insurance needs to be taken out with an insurance provider whereas a trust is set up by the founder using a trust company, an attorney or the fiduciary division of one of the major South African banks. Now that you know where to start, the next logical question becomes when?

How to talk to your teenager about money

When to start saving

Gavin says you must start saving even before your child is born! That is a tall order considering that preparing for the birth of a child alone may exhaust your available income. “The benefit of doing so is that you maximise on the compound effect of interest over the longest possible term,” he says. His statement supports the advice given on the Allan Gray website. One person that certainly understands the power of compound interest is Naphamuli Sibiya, who started planning for her daughter’s education soon after giving birth. “I’ve had an education policy with Liberty Group SA since my daughter was six months old. She turned 11 this year, and I’m quite happy with the returns,” she says. Perhaps the issue then is not that education policies don’t offer good returns, but rather that investors don’t stay in them long enough to see the desired growth. Let’s take the cost of tuition for instance. According to Gavin, a three-year university education will cost R750 000 in 18 years’ time. “Assuming that you take out an investment that gives 10% annual growth, you’d need to invest R1 250 per month for 18 years in order to afford to send your child to university,” he says. When I think of that monthly amount and the fact that my daughter is already 13, my best bet for funding her tertiary education is clearly to put in extra effort into our homework sessions so she qualifies for a bursary! In fact, let me get to it right now!